The Tricky Intersection of AI and Walled Gardens

Generative AI is already radically altering plans for how current and future SaaS offerings will generate human experiences, and how those experiences will be consumed. Keen attention to how consumers are already changing their behavior in this new environment is vital to surviving this transition.

The existential threat implicit in any arms race is that all of the humans involved will be ultimately wiped out by the arms they have competitively created, leaving behind only the weapons they invented, and the aftermath of their use.

The existential threat implicit in any automated system is that the very real and legitimate needs of the humans interacting with that automated system will ultimately be discounted out of consideration as the system optimizes for it's own efficiency.

The existential threat implicit in any walled garden system is that fundamental human rights and freedoms, of speech and privacy and choice, will be eliminated as the walled garden environment is optimized for profit.

How then to feel if a provider of a walled garden provider loudly touts their implementations of AI-driven automated systems provided for the use of their customers, while the independent use of AI-driven automated systems by those same customers to interact with that same walled garden is referred to as an arms race?

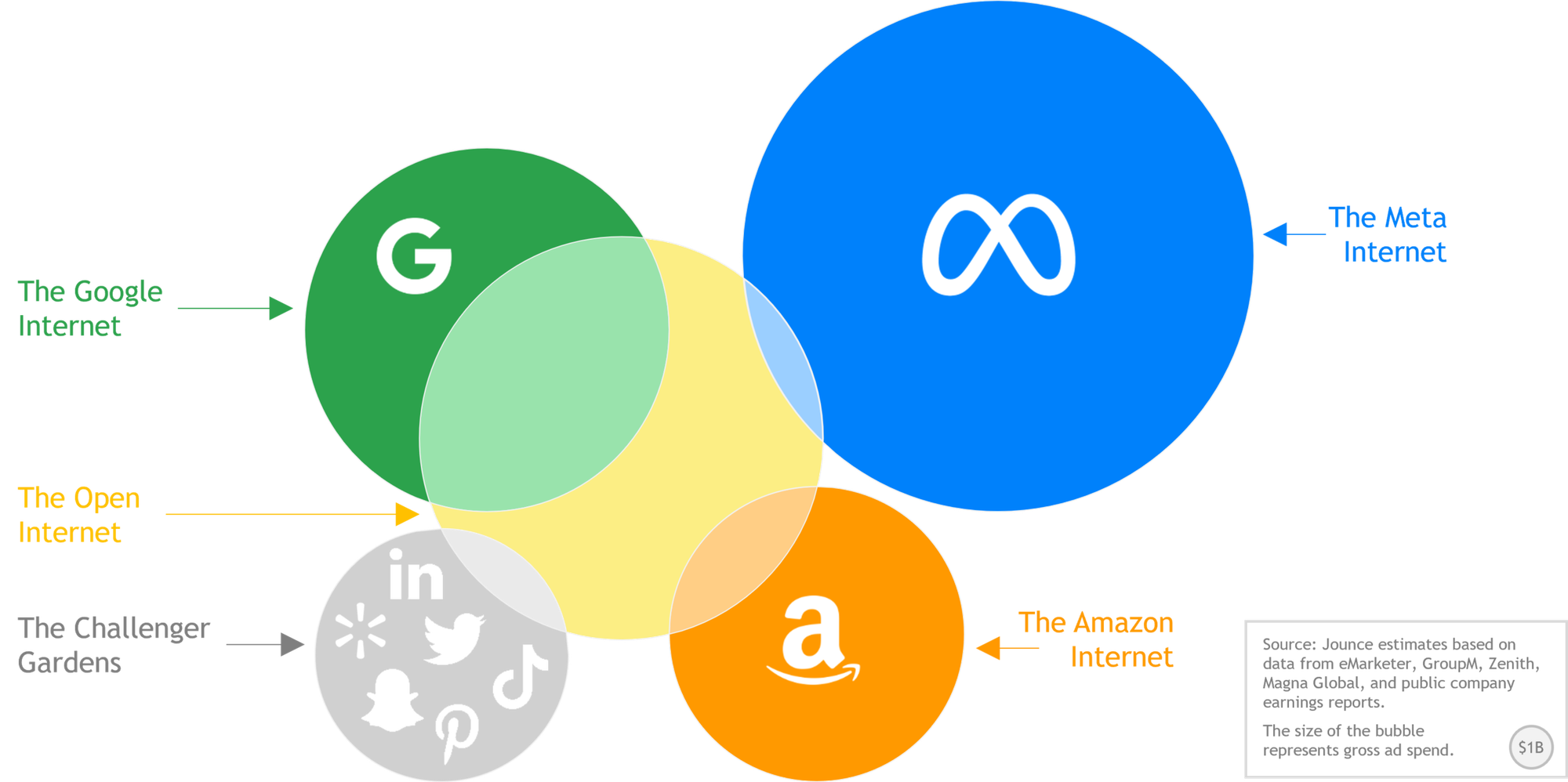

The Concentration of Attention

Over time the Attention Economy the Internet has enabled has consolidated into walled garden offerings from a few large providers which garner significantly more attention and generate significantly more revenue than all of the independent offerings of open Internet combined.

Often without realizing it, most people using the Internet today spend most of their time interacting with walled garden systems provided by one of these few dominant players.

All of the walled garden providers are aggressively integrating AI-based automated systems into their offerings for their customers to directly interact with, knowingly or otherwise.

The Industrialization of Experience

Nobody alive today remembers when every fork, every knife, every cup or glass, was made by hand, by people with specific artisanal skills, yet such a time did once exist.

Industrialization is the term we use to describe the automation of the manufacture of such goods, in factories, using machinery instead of people to perform the repetitive tasks required. In an ironic twist on the notion that 'nobody wants to work', some labor movements during the time period when this originally happened focused on the idea that such labor should not be turned over to machines, because people wanted to perform that work, but these movements ultimately failed in the face of the efficiency and scalability the machines provided.

Unlike with a factory making forks and spoons, it is much harder to scale and grow the Attention Economy when one of the key requirements to doing so is access to an ever-growing supply of actual, focused, human attention.

To create value in the Attention Economy, experiences must be offered and consumed, and yet the act of consuming such experiences, by applying for jobs or going on dates, is constrained by the very limited ability of human consumers to do more than one thing at a time.

As the Internet is now available to pretty much every human being, and the large platforms compete within a global addressable market which encompasses essentially all of humanity, attention seeking has become a zero sum game.

This is an existential challenge. The valuations of the large walled garden platforms each rely upon an assumption of infinite potential growth, even as the shared supply of people interacting with them has become clearly and painfully finite.

To continue to grow more and more valuable, platforms, which profit by providing personalized experiences to garner attention and therefore create value, must find a way to consistently provide an ever-increasing number of very personalized experiences. To make this work, these experiences are going to have to somehow be provided in a way which generates attentional value, but without the limiting requirement that the people consuming the offered experiences actually... pay attention.

So how to separate the consumption of a personalized experience from the actual experiencing of a personalized experience?

We now live in a time where glassware and utensils are cheap and abundant, but every human relationship still requires us to pay personal attention to the experience of forming and maintaining that relationship, through for example the conduct of job applications, interviews, team meetings, and first dates.

To modify this requirement of being present and engaged in the tasks of relationship management some of the walled garden providers have recently begun to suggest the future availability of 'avatars' or 'digital twins'. These are promoted as AI-powered 'agents' of the customer, which will independently interact, on behalf of the customer, with the platform and other consumers, without the customer needing to be present or to actively supervise the interactions the avatar undertakes.

In the case of Zoom, the idea is that an AI agent can attend meetings and interact with other participants of the meeting, some or all of which may also be agents, to surface and review facts, make decisions, and generate action items which are then memorialized using AI-based summarization tools.

Bumble, an online matchmaking site, suggests that encounters between AI-powered personalized 'dating concierges' could replace awkward encounters between people who do not yet know each other, simulating faithfully such an encounter to the extent necessary to establish if an actual personal encounter would be advisable or desirable.

While anyone in business who has been triple-booked for meetings on a Thursday morning can understand the temptation of the Zoom value proposition, the Bumble proposition may better illuminate the potential of automation to scale personalized experiences.

Rather than experiencing 50 first dates over the course of a year, the Bumble dating concierge could theoretically enable a person to consume 500 or 5,000 or 50,000 first dates over the course of an afternoon.

This potential for scalability, decoupled from human capacity and subject only to the financial and physical limits of the supporting platform, re-enables the critical financial assumption of infinite potential growth.

The decoupling of value creation from human capacity by enabling production, and implicitly consumption, at a mass scale, is the definition of industrialization. Using AI-powered systems, these new offerings propose nothing less than the industrialization of the manufacture and consumption of human experience.

AI and the Unintended Definition of Use

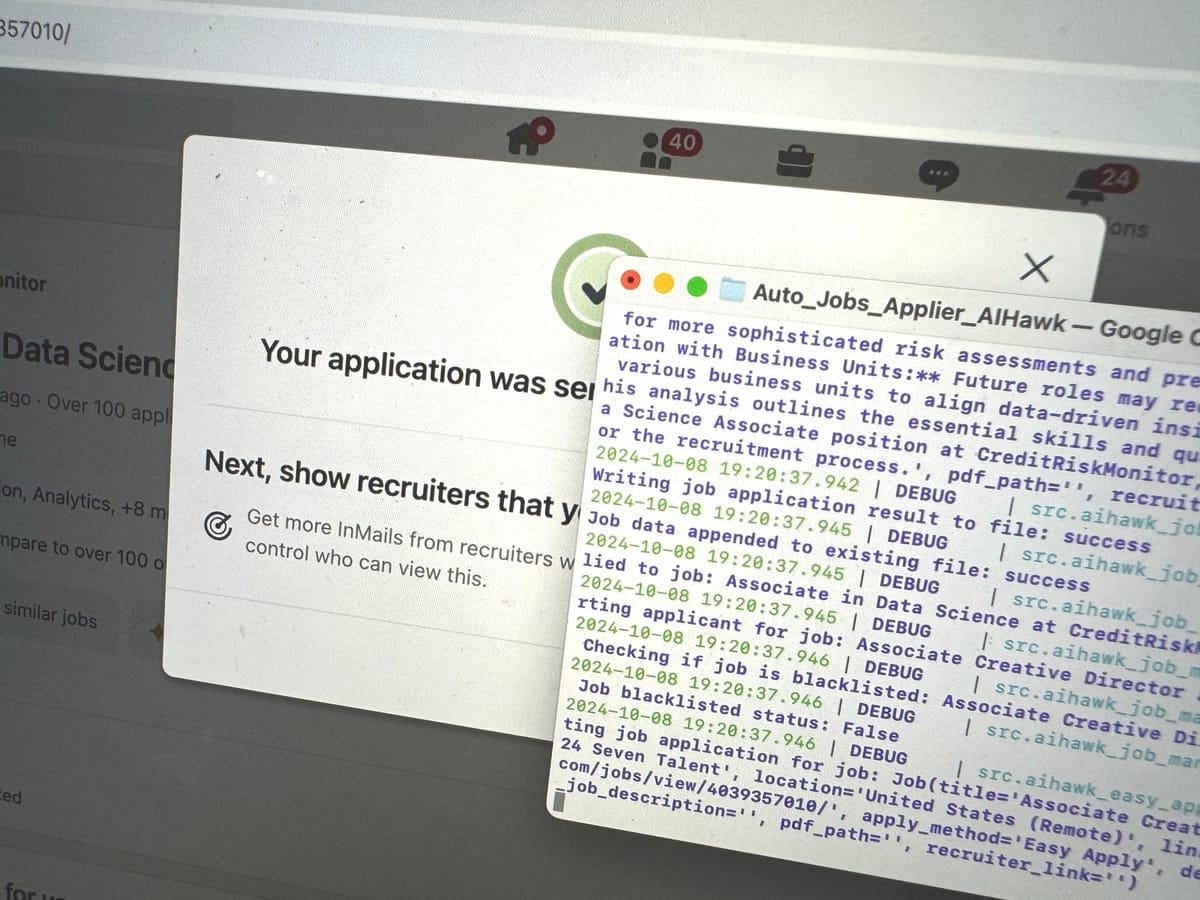

A series of videos have been circulating recently showing applications using generative AI to mass produce job applications on the LinkedIn platform. The Auto Jobs Applier Bot is one such offering:

LinkedIn, like many of the walled garden providers, has Terms of Service in place forbidding the independent use of automation by their customers, whether powered by AI or not, when interacting with their services.

LinkedIn provides a native set of AI tools which recommend potential job opportunities, allow customers to write and re-write resumes and cover letters, and generally optimize their inputs into the traditional job application process.

LinkedIn has powerful incentives not to enable the mass production of job applications. Companies which post job opportunities on the LinkedIn platform do not want LinkedIn to deliver to them mass quantities of responses. Their goal is no more than three to five well-matched candidates who can be interviewed and selected from. Enforcement of reasonable limits can be extremely pro-active.

Like finding someone to go on a first date with, filling out a job application can be fun, the first time. You get to fantasize about the possibilities while celebrating your own attractiveness. The second time can feel even easier to accomplish: the resume is written, the accounts are set up, the common questions have already been answered, so completing the task is mostly a cut and paste exercise.

LinkedIn presents an expectation the average person might fill out a few applications online, spend some quality time researching and leveraging contacts on their platform to reinforce those applications, and gain employment. Here is what the the Auto Jobs Applier Bot says about that expectation:

In the digital age, the job search landscape has undergone a dramatic transformation. While online platforms have opened up a world of opportunities, they have also intensified competition. Job seekers often find themselves spending countless hours scrolling through listings, tailoring applications, and repetitively filling out forms. This process can be not only time-consuming but also emotionally draining, leading to job search fatigue and missed opportunities.

What begins as a joyful exploration of possibilities becomes a slog through a seemingly endless thicket of small and thankless tasks producing little, and mostly negative, feedback. Stories abound of people who have manually applied to tens or hundreds of opportunities on LinkedIn, a far cry from the few carefully curated applications the LinkedIn platform envisions.

In the recent past this would be the end of the story: the platform, in this case LinkedIn, would present capabilities aligned with their worldview and business constraints: customers would be left with little choice but to conform in their interactions.

Generative AI changes this equation. Now customers have powerful and easy to use technology to assist them in implementing their own use cases for platform interactions. In the case of LinkedIn, these unsanctioned implementations provide sophisticated end-to-end workflows for 'Apply to All" strategies at volume. On dating sites "swipe-right-bots' tender automated interest in all presented potential matches.

In both of these examples the unintended use cases provide interaction at a scale not envisioned by the original implementation. Users are skipping ahead, industrializing the interaction model themselves. This presents fundamental choices for each platform, which now must decide how to respond.

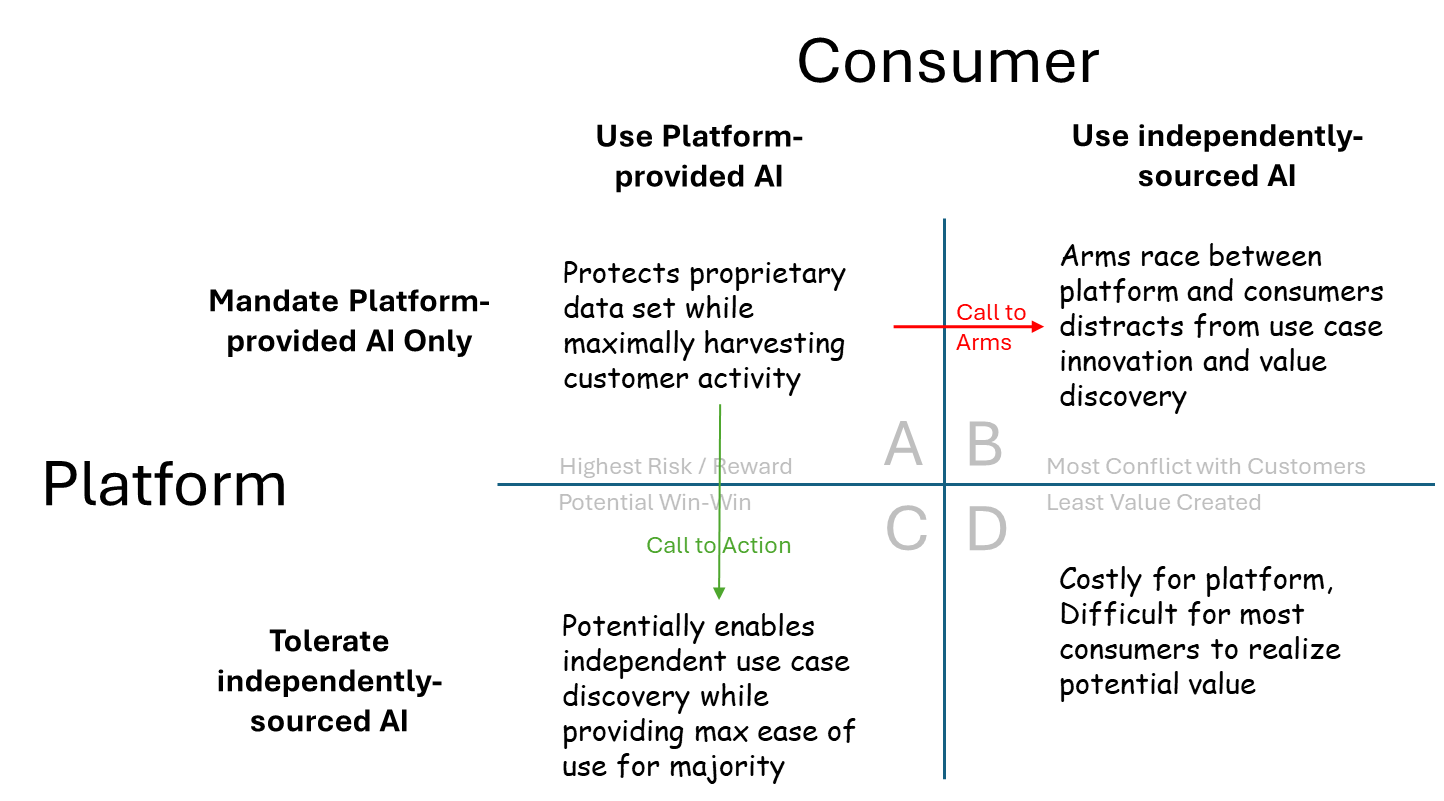

The default model for any SaaS offering is to mandate that customers must limit themselves to the platform-provided interaction model, and if AI is used to enhance that interaction model, it must be AI capability provided by the platform itself.

It is now inevitable that independently-powered AI-driven interactions will at some point appear. When they do, it can been seen as a call to arms, or a call to action.

On the call-to-arms path, independently-powered AI-driven interaction is seen as essentially harmful, not to be tolerated, and be driven from the platform. Activities such as active monitoring, counter-measures implementation, and account termination make sense in this approach.

Such an approach may be backed by business model drivers. The need to limit applications flowing from job sites to potential employers would be an example of a business model driver. In such cases the need to defend a traditional use case and model of interaction might be seen as an existential requirement, even where it creates an atmosphere of conflict with the customer

The call-to-action pathway sees the same situation very differently. The presence of unsanctioned models of interaction is seen as evidence of a feedback loop. Customer efforts are proof of unmet needs. Subsequent action might be to learn how to embrace the expressed customer need with a sanctioned and officially-provided interaction model which also respects the limits of the business model drivers.

In the case of a job site this might be an "Apply for Me' button which removes the drudgery of application completion, with guidance on 'best opportunities for me!' also subtly limiting the number of applications which can be accomplished in any given time period. In the case of a dating site, this might be the previously suggested automated simulation of an economical number of 'first dates', providing guidance on best picks for 'second' dates, improving the overall quality of the entire interaction experience, not just the portion where the customer is interacting with glass instead of actual people.

To be clear, in the call-to-action response, widespread adoption of unsanctioned interaction models is still a bad thing. Tolerating it a little, for a while, to learn from it and displace it with officially-provided interactions in a timely manner, must be the goal. Otherwise you end up in a place where control of the interaction model, the cost if creates, the data is generates, and therefore the ability to monetize, is lost. Unlimited tolerance of unsanctioned interactions is a simple recipe for business disaster.

In the call-to-action approach there is a faith that most customers will use provided interactions most of the time so long as their actual needs are mostly met. In the call-to-arms model, there is an equally strong faith that no matter how sophisticated the provided interaction model becomes, some users will always attempt to game the provided system, to the detriment of the provider and other customers.

Both beliefs are demonstrably true, and the best approach will always be some negotiated balance between these two differing views. The call-to-arms and the call-to-action should be seen as mutual, not mutually exclusive, options to be pursued. The actual mix and budget allocation for each approach is simply a question of emphasis, which can only be determined uniquely for each situation.

About Me

I'm a full lifecycle innovation leader with experience in SaaS, ML, Cloud, and more, in both B2B and B2B2C contexts. As you are implementing your value proposition, I can take a data driven approach to helping you get it right the first time. If that seems helpful to you, please reach out.